| sonoma countybeekeepers association | Click blue icon to Login |

honey bee biology

Basic Facts about Honey Bees (Apis mellifera)

Over 25,000 species of bees have been identified in the world, with perhaps as many as 40,000 species yet to be identified. In the continental United States scientists have found approximately 3,500 species of bees. Some of these bees are social and live in hives, like honey bees. Others are solitary bees, like carpenter bees or digger bees. All bees collect pollen and nectar, and many of the solitary species are essential because they pollinate plants ignored by honey bees. The scientific name for the honey bee is Apis mellifera, which means honey carrier; technically incorrect as bees carry nectar and pollen - then create honey in the hive. Within the scientific name is the genus Apis and thus beekeeping is called "apiculture" and a bee yard called an "apiary." There is good diversity in Apis mellifera with 24 known breeds. They each have different physical and behavioral characteristics such as body size, color, wing length, aggressive/docile behavior, and their susceptibility to disease. Because they all come from the same species cross-breeding can and does regularly occur, creating even more variations in the world of bees. The Spanish brought the honey bee from Europe to North America in the early 1600s, as did the English colonists later. The bees flourished and by the late 1900s, honey bees had become a common part of the environment across all of North America. Today there are more than 211,000 beekeepers tending about 3.2 million honey bee colonies in the United States.

Anatomy of a Honey Bee

Abdomen

The honey bee abdomen is composed of nine segments. The wax and some scent glands are located here in the adult. The sting is contained in a pocket at the end of the tapering abdomen in adult females.

Antenna(e)

The form of the antenna in insects varies according to its precise function. The antennae are feathery in male moths, elongated in the cockroach, short and bristle-like in the dragonfly, and bead-like in the termite. In honey bees, the segmented antennae are important sensory organs. The antennae can move freely since their bases are set in small socket-like areas on the head. Each of the antennae are connected to the brain by a large double nerve that is necessary to accommodate all of the crucial sensory input. The tiny sensory hairs on each antenna are responsive to stimuli of touch and odor.

Eyes(s)

Honey bees and people do not see eye to eye. Although honey bees perceive a fairly broad color range, they can only differentiate between six major categories of color: yellow, blue-green, blue, violet, ultraviolet, and also a color known as "bee's purple," a mixture of yellow and ultraviolet. Bees cannot see red. Differentiation is not equally good throughout the range and is best in the blue-green, violet, and bee's purple colors.

The honey bee has 2 compound eyes. Each compound eye is composed of individual cells (ommatidium, plural ommatidia). Each ommatidium is composed of many cells, usually including light focusing elements (lens and cones), and light sensing cells (retinal cells). Workers have about 4,000-6,000 ommatidia but drones have more 7,000-8,600, presumably because drones need better visual ability during mating.

Honey bees also have three smaller eyes in addition to the compound eyes. These simple eyes or "ocelli" are located above the compound eyes and are sensitive to light, but can't resolve images.

Head

The honey bee head is triangular when seen from the front. The two antennae arise close together near the center of the face. The bee has two compound eyes and three simple eyes, also located on the head. The honey bee uses its proboscis, or long hairy tongue, to feed on liquids and its mandibles to eat pollen and work wax in comb building.

Leg(s)

The honey bee has three pairs of segmented legs. The legs of the bee are primarily used for walking. However, honey bee legs have specialized areas such as antennae cleaners on the forelegs, and pollen baskets on the hind legs.

Mandible(s)

Honey bees have a pair of mandibles located on either the side of the head that act like a pair of pliers. The mandibles are used for any chores about the hive that require grasping or cutting, such as working wax to construct the comb, biting into flower parts (anthers) to release pollen, carrying detritus out of the hive, or gripping enemies during nest defense.

Proboscis

The proboscis of the honey bee is simply a long, slender, hairy tongue that acts as a straw to bring the liquid food (nectar, honey, and water) to the mouth. When in use, the tongue moves rapidly back and forth while the flexible tip performs a lapping motion. After feeding, the proboscis is drawn up and folded behind the head. Bees can eat fine particles like pollen, which is used as a source of protein, but cannot handle big particles.

Pollen Basket(s)

These are smooth, somewhat concave surfaces of the outer hind leg that are fringed with long, curved hairs that hold the pollen in place. This enclosed space is used to transport pollen and propolis to the hive. Also called a corbicula.

Pollen Press

Once the bees have gathered the pollen, they move it to the pollen press located between the two largest segments of the hind leg. It is used to press the pollen into pellets.

Rakes and Combs

Structures on the legs used to collect and remove pollen that sticks to the hairy bodies of honey bees.

Stinger

The stinger is similar in structure and mechanism to an egg-laying organ, known as the ovipositor, possessed by other insects. In other words, the sting is a modified ovipositor that ejects venom instead of eggs. Thus, only female bees can have a stinger.

The sting is found in a chamber at the end of the abdomen, from which only the sharp-pointed shaft protrudes. It is about 1/8-inch long. When the stinger is not in use, it is retracted within the sting chamber of the abdomen. The shaft is turned up so that its base is concealed. The shaft is a hollow tube, like a hypodermic needle and the tip is barbed so that it sticks in the skin of the victim. The hollow needle actually has three sections. The top section is called the stylet and has ridges. The bottom two pieces are called lancets. When the stinger penetrates the skin, the two lancets move back and forth on the ridges of the stylet so that the whole apparatus is driven deeper into the skin. The poison canal is enclosed within the lancets. In front of the shaft is the bulb. The ends of the lancets within the bulb are enlarged and as they move they force the venom into the poison canal, like miniature plungers. The venom comes from two acid glands that secrete into the poison sac. During stinging, the contents of the alkaline gland are dumped directly into the poison canal where they mix with the acidic portion. When a honey bee stings a mammal, the stinger becomes embedded. In its struggle to free itself, a portion of the stinger is left behind. This damages the honey bee enough to kill her. The stinger continues to contract by reflex action, continuously pumping venom into the wound for several seconds.

Thorax

The thorax is the middle part of the bee and is the anchor point for six legs (three pair), as well as two sets of membranous wings in the adult. Pollen baskets for carrying pollen back to the hive are located on the hind legs.

Wax Glands

Wax glands are four pairs of glands that are specialized parts of the body wall, which during the wax forming period in the life of a worker, become greatly thickened and take on a glandular structure. The wax is discharged as a liquid and hardens to small flakes or scales and sits in wax pockets. The worker bee draws the wax scales out with the comb on the inside hind leg. The wax scale is then transferred to the mandibles where it is chewed into a compact, pliant mass. The beeswax is then added to the comb. After the worker bee outgrows the wax forming period, the glands degenerate and become a flat layer of cells.

Wing(s)

The honey bee has two sets of two separate flat, thin, membranous wings, strengthened by various veins. The fore wings are much larger than the hind wings, but the two wings of each side work together in flight. Just flapping the wings does not result in flight. The driving force results from a propeller-like twist given to each wing during the upstroke and the downstroke.

Bee Biology

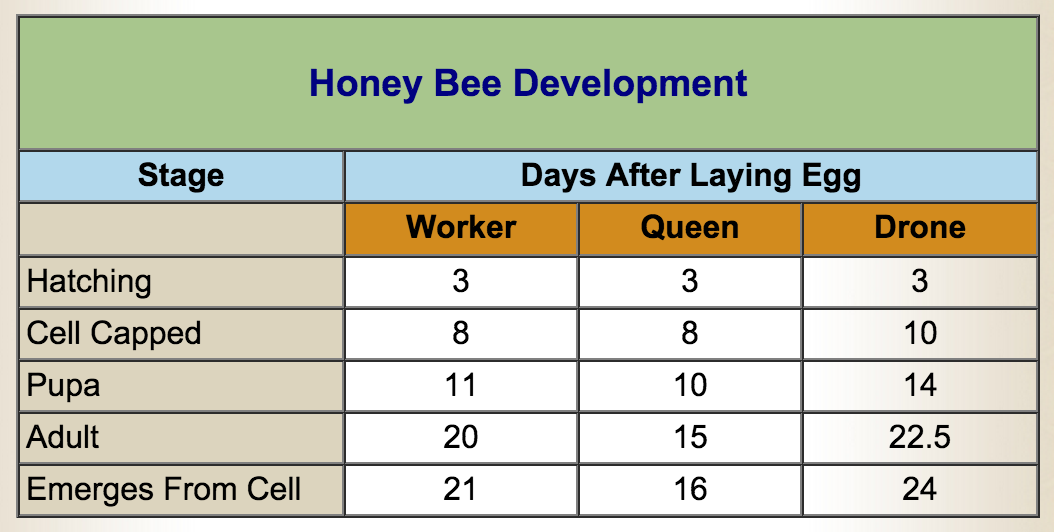

Honey bees pass through four distinct life stages: the egg, larva, pupa, and adult - a wondrous metamorphosis. Passing through the immature stages takes twenty-one days for worker bees. On the first day, the queen bee lays a single egg in each cell of the comb. The egg generally hatches into a larva on the fourth day. The larva is a legless grub that resembles a tiny white sausage. It is fed a mixture of pollen and nectar called beebread. On the ninth day the cell is capped with wax and the larva transforms into a pupa. The pupa is a physical transition stage between the amorphous larva and the hairy, winged adult. The pupa doesn't eat. On day 21, the new adult worker bee emerges.

Female worker bees make up the majority of the colony. Their jobs are tending young (larvae), making honey, making royal jelly and beebread to feed larvae, producing wax, temperature control, gathering and storing pollen, nectar, and water, guarding the hive, building-cleaning-repairing comb, as well as feeding and caring for the queen and drones. The individual job that a worker bee does depends on its age.

The male members of the colony, drones, are larger than the worker bee and make up about 1/7 of the hive population. Drones are fed royal jelly, and develop in a slightly larger cell than worker bees from unfertilized eggs. Drones remain in the pupal stage for 15 days, so they don't emerge until day 24. Drones have huge compound eyes that meet at the top of their head and an extra segment in their antennae. In comparison to worker bees, drones have wider bodies and their abdomens are rounded rather than pointed. Drones, like all other male bees and wasps, do not have stingers.

In most circumstances there is only one queen in a honey bee colony. She is slightly larger than a worker bee, with a longer abdomen. She does not have pollen baskets on her legs. Eggs destined to become queens are laid in larger cells and these larvae are fed only royal jelly. The adult queen's sole duty is to lay eggs, up to 2,000 a day! She is fed by the workers and never leaves the hive except to mate.

Queen bees also have stingers and use them in battles with each other for dominance of the colony. If a new queen emerges from her incubation cell and is detected by the current queen, the "old lady" often goes over and kills her rival. In this way, the stability of the colony is maintained. When a queen gets old or weak and slows her production of queen substance, she is generally replaced by a new queen. New queens are also produced in colonies about to swarm.

Virgin queen bees take what is known as a "nuptial flight" sometime within the first week or two after emerging from the pupal chamber. In this flight, the new queen leaves the hive and begins to produce a perfume-like substance called a "pheromone." The drones in the area are attracted to the pheromone and the queen will mate with as many as 20 of them while in mid-air. After mating, the drones die.

Once the queen has mated, she heads back to the hive to start laying eggs in beeswax chambers that the workers have created especially for this purpose. A queen can lay her own weight in eggs every day and, since she can maintain the sperm she has collected for her lifetime in a special pouch in her body, she can continue laying eggs indefinitely. The fertilized eggs laid by a queen become female worker bees and new queens. The queen also lays some unfertilized eggs, which produce the drones. Since they come from unfertilized eggs, the drones carry only the chromosomes of the queen.

The drones could be called the couch potatoes of the insect world. While they wait for an opportunity to mate with a virgin queen they are fed and cared for by workers, and only occasionally fly out of the hive to test their wings. If no opportunity to mate arises by autumn, they are ejected from the nest by the workers and left to fend for themselves.

On average, queen bees live for about a year-and-a-half, although some have been known to survive up to six years. While she is alive and active, the queen is constantly cared for by workers acting as attendants.

When the colony starts to become too crowded, some of the bees split off to form a new colony. This is called "swarming." Swarming occurs when part of the colony breaks off with the old queen and flies away looking for another place to call home. First the eggs for new queens are laid in their special larger cells so that the remaining colony can have a new queen after the swarm. The bees engorge themselves on their honey reserves before leaving so as to have sufficient energy to make it to a new location. When the swarm occurs, about half the colony leaves with the old queen, leaving the remaining half to wait until the new queen hatches, thereby making two colonies from one. There can be multiple swarms from one hive, since new queens can also emerge and fly off with part of the worker force.

What Bees Eat

Bees may fly long distances (up to six miles) in search of food and may be quite far from home when they are seen foraging in the flowers near by.

The worker bees gather pollen and nectar from flowers to feed to colony. Nectar is the sweet fluid produced by flowers to attract bees and other insects, as well as birds and mammals. Worker bees drink the nectar and store it in a pouch-like structure called the crop. They fly back to the hive and regurgitate the nectar to other "house bees". The house bees mix the nectar with enzymes and deposit it into a cell where it remains exposed to air for a time to allow some of the water to evaporate. The result is honey.

Honey bees are covered in tiny little hairs and while they are foraging in flowers the pollen sticks to the hairs. The bees groom the pollen, moving it to their hind legs and into pollen baskets. Bees returning to the hive will often have bright yellow or greenish balls of pollen hanging from these baskets.

During those hard times when there are few foraging opportunities, bees sometimes raid other, weaker colonies looking for honey to steal. The robber bees cannot enter a different hive unnoticed. Guard bees at the hive entrance usually try to fight off invaders in stinging duels.

In addition to food, honey bees gather water for use in cooling the inside of the nest on hot days. They also use water to dilute the honey when they feed it to the larvae. Occasionally, honey bees collect the sticky resin and gum of trees and work into a substance called propolis. They used propolis to plug unwanted openings in the hive so that mice and pests such as wax moths or ants cannot get inside. The bees also spread a thin coating of propolis on the interior of the hive to protect against disease. When working a hive, the beekeeper uses a hive tool to pull apart the frames that may be stuck together with propolis.

Bee Senses

Smell

Bees "smell" many things. Guard bees sit or hover near the hive entrance and "smell" other bees trying to enter the hive. If the bees don't have the correct odor of that particular hive they are expelled. The new virgin queens produce a special odor called a sex pheromone to attract drones during the mating flight . Bees also use odors to help locate their hive or their new home after swarming. To humans this pheromone smells lemony.

When a bee stings, she releases an odor called an alarm pheromone to alert others to the danger. This alarm pheromone smells like bananas and attracts other bees to come to the defense of the hive. This pheromone stays on clothing, so if you are stung you should wash your clothing before wearing it again.

The queen bee has her own pheromones in addition to the smell she produces when ready to mate. She also maintains behavioral control of the colony by a pheromone known as the "queen substance." As long as it is being passed around, the message in the colony is that "we have a queen and all is well." When a beekeeper wants to re-queen a colony by introducing a queen from another source, he or she must place the queen in a cage within the colony for up to five days in order for the worker bees to get used to her odor.

Sight

Honey bees and people do not see eye to eye. Humans see the colors of the rainbow; red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet (otherwise known as ROY-G-BIV). Although honey bees have a fairly broad color range, they do not see red and can only differentiate between six major categories of color, including yellow, blue-green, blue, violet, and ultraviolet. They also see a color known as "bee's purple," a mixture of yellow and ultraviolet. Differentiation is not equally good throughout the range and is best in the blue-green, violet and bee's purple colors.

Taste

Honey bees have been found to be able to distinguish between sweet, sour, bitter and salt, and thus have a sense of "taste." Bees are more sensitive to salts than humans, but less sensitive to bitter flavors.

Touch

Honey bees use their antennae to gauge the width and depth of cells while constructing comb. They also communicate via touch during bee dances.

Swarms

What is a honey bee swarm?

Honey bee swarms are one of the most beautiful and interesting phenomena in nature. A swarm starting to issue is a thrilling sight. A swarm may contain from 1,500 to 30,000 bees including workers, drones, and a queen. Swarming is an instinctive part of the annual life cycle of a honey bee colony. It provides a mechanism for the colony to reproduce itself.

What makes a honey bee colony swarm?

Overcrowding and congestion in the nest are factors which predispose colonies to swarm. The presence of an old queen and a mild winter also contribute to the development of the swarming impulse. Swarming can be partially controlled by a skilled beekeeper; however, not all colonies live in hives and have a human caretaker.

When do honey bees swarm?

The tendency to swarm is usually greatest when bees increase their population rapidly in late spring and early summer.

Are honey bee swarms dangerous?

NO - honey bees exhibit defensive behavior only in the vicinity of their nest. Defensive behavior is needed to protect their young and food supply. A honey bee swarm has neither young nor food stores and will not exhibit defensive behavior unless unduly provoked.

What should homeowners do about a honey bee swarm on their property?

When honey bees swarm they will settle on a tree limb, bush, or other convenient site. The swarm will send out scout bees to find a cavity to nest in and will move on when a suitable nesting site is found. Rarely, swarms may initiate comb construction in the open if a suitable cavity cannot be found. You may want to call a local beekeeper to see if they would like to collect the swarm.

A swarm in May - is worth a load of hay.

A swarm in June - is worth a silver spoon.

A swarm in July - isn't worth a fly.

How does a beekeeper go about capturing a swarm of honey bees?

A swarm is looking for a new nesting site. A beekeeper can capture a swarm by placing a suitable container, such as an empty beehive, on the ground below the swarm and dislodging the bees at the entrance to the hive. The bees will begin to move into the hive which can be removed after dark to the beekeeper's apiary. You can observe the bees scent-fanning at the entrance to signal the entrance to the new nest as the bees march into their new home. If for some reason the queen does not go into the new hive, the bees will abandon it and form a cluster where she lands.

What type of nesting sites will honey bees seek?

Honey bees are cavity nesters and will seek a cavity of at least 15 liters of storage space. Hollow trees are a preferred nesting site. Occasionally, bees will nest in the hollow walls of buildings, under porches, and in other "man-made" sites if they can find an entrance to a suitable cavity.

What can be done if a honey bee swarm establishes itself in an undesirable place?

Honey bees are beneficial pollinators and should be left alone and appreciated unless their nest are in conflict with human activity. If honey bees nest in the walls of a home, they can be removed or killed if necessary; however, it is advisable to open the area and remove the honey and combs or rodents and insects will be attracted. Also, without bees to control the temperature, the wax may melt and honey drip from the combs. After removal, the cavity should be filled with foam insulation as the nest odor will be attractive to future swarms. You may want to seek the assistance of a professional beekeeper. Nests should be removed promptly from problem sites. After several months, they may have stored a considerable amount of honey. You can prevent swarms from nesting in walls by preventive maintenance. Honey bees will not make an entrance to a nest. They look for an existing entrance, so periodic inspection and caulking is all that is necessary to prevent them from occupying spaces in walls.

Why are we observing fewer swarms than in previous years?

In the 1980s, two mites that parasitize honey bees were introduced into the U.S. They have spread throughout the states and have eliminated many wild or feral colonies. In addition, the number of colonies managed by beekeepers has declined during the past decade. Farmers and gardeners producing tree fruits, small fruits, forage legumes, oil seed crops, and vegetable crops requiring bee pollination need to consider pollination requirements as once abundant honey bee pollinators are no longer something they can take for granted. Managed honey bee colonies may be needed to assure adequate pollination of these crops.

In recent years, honey bees have come under attack from multiple pests, and the number of honey bee colonies has been on the decline. Tracheal mites and Varroa mites are two of the more common pests which devastate honey bee colonies. It is reported that over 2/3 of the produce crops which we consume are directly pollinated by honey bees - they're a very important part of our world, and shouldn't be treated like pests. Calling a beekeeper to capture your swarm helps to restore the population of bees.

What to expect...

A beekeeper will arrive and assess the situation. The beekeeper will have a swarm capturing box, the specific design of which can vary considerably. In the case of tree (which is a common landing place for a swarm) and fence/exterior swarm clusters, the beekeeper will typically jostle the swarm of bees into the box, which might take a few attempts (but is quite spectacular), and then will set the box up and leave it for the bees to congregate in until after sundown, when the beekeeper will return to close up the box and transport it.

Structural extractions - removing bees from inside a wall for instance - are understandably more involved, and involve established colonies, rather than a swarm in transit. The process may require removal of siding or interior drywall or plaster. It can often be a multi-day process.

A swarm capture is an amazing sight to watch - please do so at a safe distance. Some beekeepers might even bring an extra "bee suit" and/or veil, and if you're so inclined, you might ask about this if you want to lend a hand or take a closer look. Not all beekeepers will feel comfortable with the distraction, so please respect the beekeeper's decision should they decline the request. Beekeepers are happy to answer questions and explain the process. If you'd like to take photographs while the beekeeper is working, please ask the beekeeper first.

Provided that you do not irritate the bees (swatting at them is a good way to do that), stinging risk should be minimal. If you do get stung, the most important thing to do is remove the stinger as fast as possible, which will minimize venom transfer. A scraping motion is most effective, and is preferred over trying to grasp the stinger to remove it, but either way, the quicker you remove the stinger with venom sac, the less venom will be transferred, and the less irritation you will subsequently experience.

Bee Safety

Beekeepers have learned to respect and honor the honey bee. When this happens a new relationship begins - they become sensitive to each other's presence. Most beekeepers enjoy handling and observing bees and may comfortably do so without wearing protection. Generally bees are gentle as they go about their business of foraging and hive building. Slow and methodical movements should be adhered to when around bees, let them know what you are doing. You can even talk or sing to them.

Bee Alert!

The best safety advice is to avoid an encounter with unfriendly honey bees. Be alert for danger. Remember that honey bees sting to defend their colony, so be on the look out for honey bee swarms and colonies. Be alert for bees coming in and out of an opening such as a crack in a wall, or the hole in a water meter box. Listen for the hum of an active bee colony. Look for bees in holes in the ground, holes in trees or cacti, and in sheds. Be extra careful when moving junk that has been lying around.

Be alert for bees that are acting strangely. Quite often bees will display some preliminary defensive behavior before going into a full-fledged attack. They may fly at your face or buzz around over your head. These warning signs should be heeded, since the bees may be telling you that you have come into their area and are too close to their colony for comfort, both theirs and yours!

When you are outdoors in a rural area, park, or wilderness reserve, be aware of your surroundings and keep an eye out for bees the way you would watch out for snakes and other natural dangers. But don't panic at the sight of a few bees foraging in the flowers. Bees are generally very docile as they go about their work. Unless you do something really outrageous, such as step on them, they will generally not bother you.